His soft voice, silver moustache, and gentle demeanour gave George Bizos, the lawyer who famously defended Nelson Mandela and who has died aged 92, the appearance of a retired country doctor.

And indeed, in person, he was famously courteous and deferential. No airs and graces – and no easy retirement – for a man who could easily have basked in his hard-earned reputation as a pivotal figure in South Africa’s long struggle against apartheid.

But for most struggle stalwarts of his generation, a life of service meant just that – a life.

And George Bizos remained active and outspoken into his tenth decade.

The air of quiet politeness that accompanied him to the end was not false.

But it masked a fierce and uncompromising devotion to justice and human rights, and a belief that the law was a weapon which, used correctly, had at least as much power as guns and speeches.

I met him many times in the last two decades of his life, to interview him about stolen elections in Zimbabwe – his simple maxim that an election is pointless unless both sides accept the result, stuck with me – about his mediating role in the difficult family battles over Mandela’s will, and about his determination to fight for justice for the families of those shot by police in the Marikana killings of 2012.

Barrister’s instincts

But it is a trip I made with him a decade ago, to revisit his first law office, in central Johannesburg, that comes to mind now. I remember following Bizos as he shuffled slowly across Fox Street, over to a shabby-looking café.

Smiles of recognition followed in his wake as he moved through the lunchtime crowd.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESThe Chinese man behind the till was complaining about trouble in the area.

“There’s a derelict building on the next block. Chancellor House. It’s full of criminals,” he said.

Bizos’ crumpled back straightened. His barrister’s instincts alerted.

“That house,” he explained patiently, “is occupied by dozens of squatters who have no alternative accommodation.

“They should not be casually categorised as criminals.”

It was a good 50 years since Bizos had first bought lunch at this café.

He and his friend Nelson Mandela used to come at least once a week to grab a couple of pies and take them back to Mandela’s office around the corner.

As a white man – born in Greece – Bizos could have eaten at the café.

But in those days black people were banned from sitting down here.

On the way out that day, two men in workmen’s clothes stopped Bizos and asked if they could shake his hand.

‘A lot of memories’

One block down Fox Street, opposite the magistrate’s court, was the derelict, three-story building the Chinese man was complaining about.

The walls were blackened by fire. Half a dozen young men stood outside it. There was a strong smell of marijuana and of rubbish.

“A lot of memories,” said Bizos, smiling at the crowd then slowly climbing the pitch-black stairwell of Chancellor House, up to the water-logged landing on the first floor.

At the far end – a makeshift door opened into what was once Mandela’s office – the very first black law firm in South Africa – a place that used to be besieged by clients.

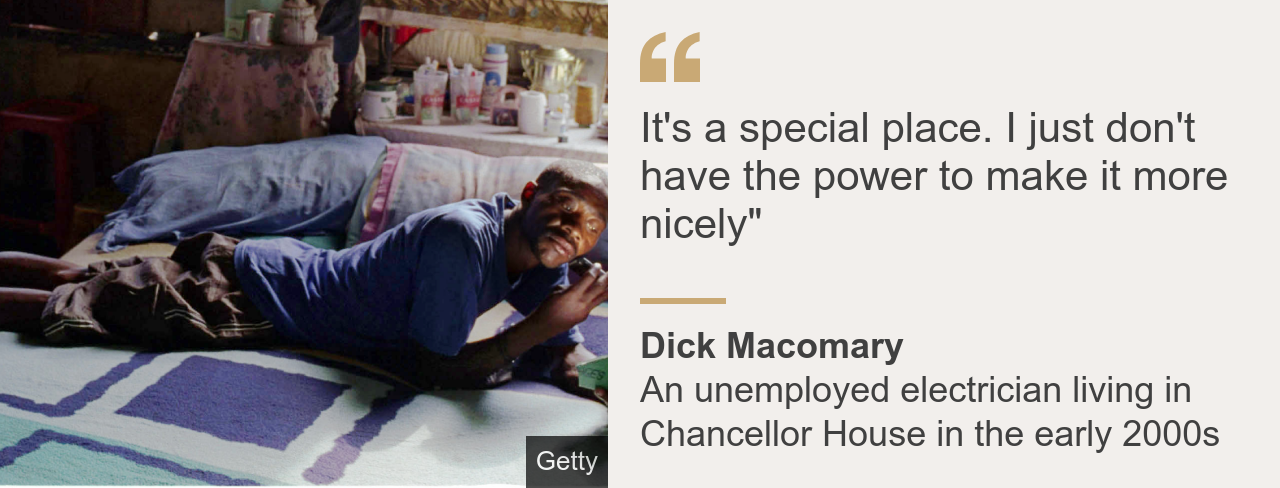

It was occupied at the time by a 38-year-old old unemployed electrician – Dick Macomary – and his growing family. There was a mattress on the floor. Pots and pans. Some clothes drying by the boarded-up windows.

“Sorry,” said Mr Macomary, clearing away some old newspapers. “It’s a special place. I just don’t have the power to make it more nicely.”

Bizos looked around in the gloom.

“If we brought Mr Mandela here now, it would break his heart,” he said.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESBizos pointed to a corner of Mr Macomary’s bedroom.

“We want to put computers here and a library over there,” he said.

The plan was to turn Chancellor House into a legal resource centre for young black lawyers.

“Not a mausoleum, but something living. Something to honour Mr Mandela. I hope to see that happen in my lifetime – and his,” said Bizos.

Mr Macomary nodded enthusiastically.

‘I hate generalisations’

But there had been delays. The city council was supposed to offer alternative accommodation to the 60 or so people living in Chancellor House.

But legal negotiations had dragged on for more than a decade.

“This is not good for you, and it is not good for Mr Mandela. The city council has a reputation for being a little tardy, to say the least. It is almost a malaise. Nobody seems to take responsibility,” Bizos sighed.

I asked him if the fate of Chancellor House said something about modern South Africa – its growing struggles with corruption, poor service delivery, and a stagnant economy.

But he cut me dead.

“I hate generalisations,” he said.

And he was right, of course. Chancellor House would eventually be renovated as he had hoped.

A life of service

- Bizos arrived in South Africa in 1941 at the age of 13, fleeing Nazi-occupied Greece

- Fell out of education for a while after arriving in Johannesburg with no English

- He later trained as a lawyer, completing a degree in 1950

- Studied at Johannesburg’s University of Witwatersrand, where he met Nelson Mandela, a fellow law student

- Represented some of the country’s best known political activists during the apartheid years

- Part of the team that defended Mandela and others during the 1964 Rivonia Trial when they were accused of seeking to overthrow the apartheid government

- Credited with adding the words “if needs be” to Mandela’s famous speech at the trial, in which he said he was prepared to die

- Became one of the architects of South Africa’s new constitution after the end of apartheid in 1994

- Represented families of anti-apartheid activists who had been killed during apartheid at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- In 2004 got Zimbabwe’s late opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai acquitted on charges of plotting to kill then-President Robert Mugabe

- In one of his last major trials, he secured government payouts for families of 34 workers at Marikana mine killed by South African police in 2012

We walked east along Fox Street towards the central business district.

“Look at this,” he said, pointing at Main Street. “It used to be a slum. Now it’s like a French boulevard with cafés on the pavements.”

You might also be interested in:

`

And it was true – large chunks of central Johannesburg were, and still are, changing dramatically.

The businesses that were chased out by crime in the 1990s are now coming back.

A group of lawyers standing outside the magistrate’s court all turned and smiled at Bizos as he walked past in the sunshine.

“I’m optimistic about South Africa,” he said.

“But you must bear in mind that I was optimistic in the 40s, and the 50s, and 60s, and so on. I have always been optimistic.”

Source: BBC

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More