IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

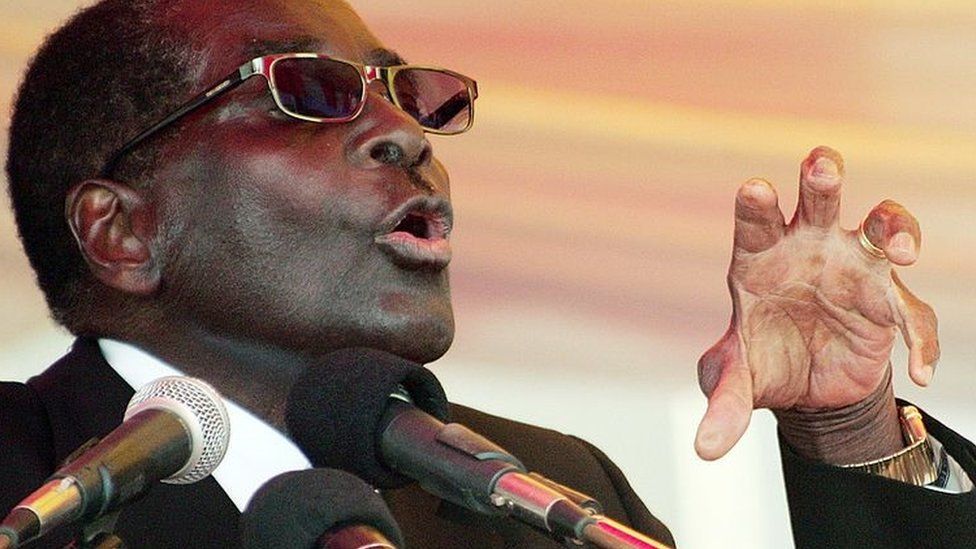

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIn our series of letters from Africa, Zimbabwean journalist-turned-barrister Brian Hungwe writes that long-serving ruler Robert Mugabe, who died in 2019, seems to be causing trouble from beyond the grave.

Robert Mugabe’s relatives say he died a bitter man nearly two years after he was forced to hand over power to current President Emmerson Mnangagwa – and his bitterness, even in death, is creating feuds.

In an African traditional context, the dead can speak, often through a vengeful spirit that is believed to respond violently against erstwhile tormentors. Therefore, the spirit needs to be appeased to avoid the risk of being destroyed by it.

If Mugabe’s temperament in real life could be measured against the intensity of his supposed potential vengeful spirit, it would be like the molten lava that has recently been spewing from Mount Nyiragongo in the Democratic Republic of Congo, consuming everything in its path.

Mr Mugabe was a Catholic, partly raised by missionaries who had immense influence in his upbringing. But he never abandoned all of the traditional beliefs.

‘Spiritual power’ of political hero

Often at the national shrine where independence-era heroes are buried, Mugabe used to invoke the “spirit medium” of the liberation war hero, Mbuya Nehanda, who was hanged by the British colonialists towards the end of the 19th Century.

She is believed to have said that her bones would rise against the white colonial settlers. This became a spiritual mantra, feeding into African nationalist resistance.

Last week, President Mnangagwa unveiled a statue of Nehanda in the heart of the capital, Harare.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPA

IMAGE COPYRIGHTEPASome saw it as a ploy to capitalise on the legacy created around her, given that his plan to have his 95-year-old predecessor buried in a special grave at Heroes Acre had been stymied.

This would have given him the opportunity to visit the shrine, and invoke Mr Mugabe’s spirit for political gain – despite the fact that he ousted his former comrade from power in 2017, thwarting then-First Lady Grace Mugabe’s ambition to become the next president.

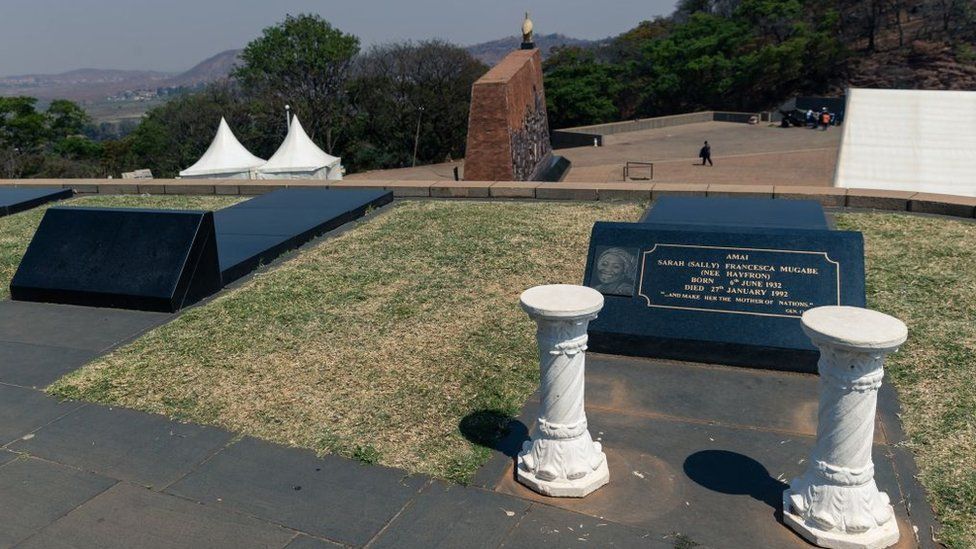

Mrs Mugabe denied Mr Mnangagwa the opportunity, insisting that it was the former president’s wish to be buried at his family home in Zvimba, next to his mother Bona.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

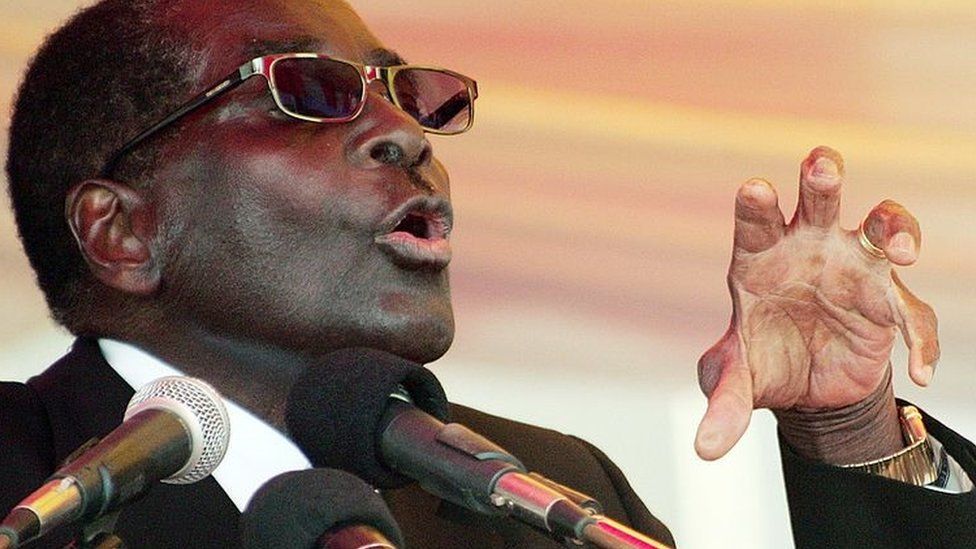

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESAnthropologist Joost Fontein – author of The politics of the dead in Zimbabwe: Bones, Rumours and Spirits – offers a different explanation for the former first lady’s decision.

“She didn’t want him buried next to Sally [Mugabe’s first wife] because she knows Sally remains much more popular than she will ever be.

“But also she probably seeks to deny the new regime the legitimacy that Mugabe’s burial at Heroes’ Acre would bestow upon them,” he says.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESThese tensions burst into the open last month, when a traditional chief in Zvimba ruled that Mrs Mugabe was guilty of breaking traditional norms by burying her husband in the courtyard of his home.

Mrs Mugabe – who is reportedly unwell, and in Singapore – did not attend the hearing, but the chief ordered her to pay five cows and a goat as a fine.

The former president’s nephew Leo Mugabe dismissed the ruling, saying the chief had no jurisdiction over the matter.

Order to surrender Mugabe’s clothes

Nevertheless, the row is not surprising. Prof Fontein points out that in Zimbabwe the significance of death, bones, and spirituality can affect politics.

“A lot of the controversies around Mugabe’s burial have to do with the system of national commemoration that the former president himself had such a significant role in creating and in which he invested much energy,” he says.

In his ruling, the traditional chief ordered Mr Mugabe’s reburial at Heroes Acre, and for his widow “to gather [his] clothes and all his belongings and surrender them on or before the 1st of July”.

The political cult that Mr Mugabe built around himself lives on, with Zimbabwe’s founding father still ruling from his grave”

Historian Terence Ranger says the significance of the “custodianship” of a dead person’s remains lies in the perceived protection they can give the living.

Mr Mugabe’s nephew, Patrick Zhuwao, adds that a sceptre allegedly given to the former president by 16 traditional leaders anointing him as Zimbabwe’s leader may also be behind the row.

It is this staff, he told South Africa’s public broadcaster, SABC, that Mr Mnangagwa wants.

Fear of witchcraft

Mr Mnangagwa’s spokesman George Charamba, who held the same position under Mr Mugabe, scoffed at the suggestion that the former president had a sceptre, let alone that his successor wanted it.

“Turning such an anti-feudal revolutionary into an anachronistic Monarch!!! A bit of enlightenment helps, dear Zimbabweans!!!!” he tweeted under the name Jamwanda.

In the complex realm of traditional politics, bones can also be abused for witchcraft.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFP

IMAGE COPYRIGHTAFPThere have been long-standing rumours that Mrs Mugabe insisted on burying her husband at the family home to rule out the possibility of her enemies exhuming his bones to harm her and her children.

There has also been talk that she wants to retain custodianship of her husband’s bones in order to build an aura of almost untouchable power around herself – power that Mr Mugabe demonstrated during most of his 37-year-rule, and which he had now relayed to her through the “spirit medium”.

So the political cult that Mr Mugabe built around himself lives on, with Zimbabwe’s founding father still causing trouble from his grave.

BBC.COM

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More