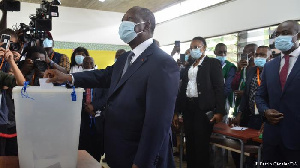

Ivory Coast’s ruling party Rally of Houphouetists for Democracy and Peace (RHDP) warned the political opposition, which boycotted the presidential election of October 31, against any “attempt to destabilise” the country. At least five people died over the weekend in election-related violence.

The warning came in the wake of a call by the opposition for a “civilian transition” from President Alassane Ouattara’s government, which it considers illegitimate. Opposition leader Pascal Affi N’Guessan told reporters: “We consider that there has been no election in Cote d’Ivoire. What Ouattara did is constitutional robbery.”

After the unexpected death, on July 8, of Prime-Minister, Amadou Gon Coulibaly, which Ouattara had handpicked to run for his succession, the 78-year-old president changed his mind on retirement. He argued that the new constitution, which imposes a two-term limit to the presidency, did not apply to his previous mandates. Thirty people died in ensuing protests.

‘Ouattara will have his third term’

Preliminary results pointed to an overwhelming majority for Ouattara.

“In the areas where President Ouattara is particularly popular and his party is predominant, the figures seem to me quite credible,” analyst Paul Melly of the London-based think tank Chatham House told DW.

Melly stressed that the boycott of the elections by the opposition candidates Pascal Affi N’Guessan and Henri Konan Bedie benefited the incumbent.

Much will depend on the election’s turnout to decide how legitimate Ouattara’s mandate is. But, at this point, the question is academic.

“What’s going to happen is very simple: there has been an election of sorts and President Ouattara will have his third term of office,” said DW correspondent Bram Posthumus. “The idea that this party was going to relinquish power has always been a non-starter.”

The opposition maintained that the election boycott was successful, invalidating the polls. Not so, said political analyst Sylvain N’Guessan: “There is no law in Cote d’Ivoire that imposes a participation rate to validate elections.”

Ivorians want peace

Fearing a repeat of the violence 10 years ago, thousands of Ivorians left urban centres for their villages before the polls. After the 2010 presidential vote, 3,000 people died in the violence resulting from President Laurent Gbagbo’s refusal to accept defeat at the hands of Ouattara. On Monday, Abidjan was back to its normal busy self.

“During the weekend it was like a ghost town, which is highly unusual for this city of six and a half million people,” said Posthumus.

In the streets of the capital, passersby told DW of their fears. “We are scared, we don’t know what’s going to happen. We are praying that the different presidents listen to us,” one man said. “We need God. We need peace, happiness,” a woman added.

“People are sick and tired of this whole political game and they want to carry on with their businesses,” Posthumus said, explaining why the population will not allow itself to be mobilized in protests to the extent that happened in 2010.

Violence can be averted

“There are no certainties, but it seems unlikely that violence will develop on the scale it did ten years ago,” Paul Melly agreed. The country is not as dangerously divided as it was then. The current government put an end to the military split resulting from the civil war — which opposed the government army in the south to pro-Ouattara rebels in the north — by merging them into a single military structure.

Two risks remained: localized protests with things getting “out of hand and then the security forces overreact,” and ethnic violence, Melly said. At least some of the recent violence resulted from protests which degenerated into clashes between ethnic communities that back rival political factions.

Already the international community is putting pressure on Ivory Coast’s political elites to behave themselves. “The chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Fatou Bensouda, remarked the other day that the sort of events that can sometimes happen in post-election violence are the sort of things that need people to be brought before the ICC. So that was a very clear warning,” Melly said.

International pressure

Ivory Coast’s neighbours are also certain to put pressure on Abidjan to prevent a new crisis. Apart from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the region is plagued by jihadist attacks in the Sahel, a putsch in Mali, a disputed election in Guinea and unrest in neighbouring Nigeria.

Political analyst Fahiraman Rodrigue Kone, of the African Security Sector Network, believes that the only way forward in Ivory Coast is a national dialogue. “Whoever is elected President will have to make the effort to guarantee, once and for all, a real reconciliation process,” he said.

Bram Posthumus does not believe that the opposing parties will come together any time soon. “The rhetoric coming out of both camps has been highly antagonistic,” he said.

A dialogue in the offing?

Analyst Paul Melly is more sanguine. From his Belgian exile, former President Laurent Gbagbo— who was banned from running in the presidential election — has indicated a willingness to negotiate, by stressing the importance of talks, he said.

Ouattara has also given some indications that he is considering a dialogue.

“There could be a situation where Mr Ouattara opens up scope for some sort of discussion. It will be interesting to see what he is willing to offer the opposition as an incentive to engage in discussion with him,” expert Melly said.

Recently, Ouattara hinted at a possible constitutional amendment to limit the age of the president, thereby reacting to increased calls for power to be handed over to a younger generation.

“We may see a bit more negotiation, a bit more flexibility that one might expect,” Melly concluded.

Source: dw.com

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More