The announcement by Mahama about Women’s bank proposal seems more like a broad, populist gesture rather than a carefully crafted strategy with clear, measurable outcomes

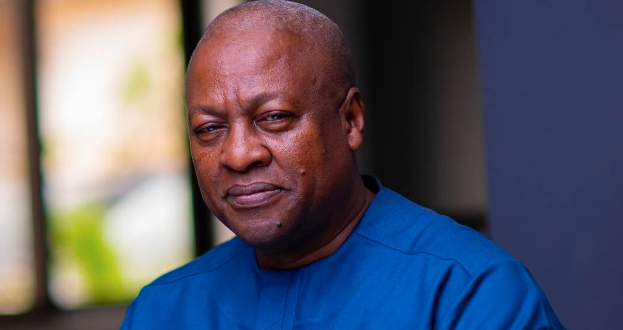

Former President John Mahama’s recent pledge to establish a Women’s Bank if elected has ignited debate across Ghana. While the proposal is ostensibly aimed at addressing gender-specific financial challenges, it prompts several critical questions: What is the true motive behind this policy?

Is it a reactionary move or a strategic initiative? How will this proposed Women’s Bank differ from existing schemes like MASLOC? And what will become of Women’s World Banking Ghana (WWBG)?

At its core, the former president claims the proposed Women’s Bank aims to empower women economically by offering tailored financial products and services.

However, the proposal lacks specifics on how it will address the unique financial needs of women that are not currently met by existing institutions.

The announcement seems more like a broad, populist gesture rather than a carefully crafted strategy with clear, measurable outcomes. The timing of this proposal raises eyebrows. Election cycles often see promises of new institutions or policies designed to sway key demographics.

Mahama’s pledge could be perceived as a reactive move to current socio-economic issues or an attempt to court women, and voters, with a proposal that lacks substantial groundwork. The absence of detailed implementation plans suggests this may be more a knee-jerk reaction than a well-thought-out initiative.

The Microfinance and Small Loans Centre (MASLOC) was created to serve underbanked populations, including women. If the Women’s Bank is to surpass MASLOC in effectiveness, it must address MASLOC’s limitations, such as inadequate funding, political interference, and operational inefficiencies.

Without a plan to overcome these challenges, the Women’s Bank risks becoming another underperforming entity rather than a transformative force. While a Women’s Bank could potentially enhance access to credit, promote financial literacy, and encourage savings among women, these benefits depend heavily on the bank’s operational model, governance, and ability to remain politically neutral.

The current proposal lacks concrete plans on how these goals will be achieved and sustained, raising concerns about its practicality and unique value proposition. Women’s World Banking Ghana (WWBG) already provides crucial financial services to low-income women.

The proposed state-sponsored Women’s Bank could either complement or compete with WWBG. If not carefully integrated, this new bank could result in resource duplication and market fragmentation. The proposal does not address how it will align with or enhance the efforts of WWBG, leaving a gap in strategic planning.

John Mahama’s promise to establish a Women’s Bank underscores the important issue of women’s financial inclusion. However, the proposal, as it stands, appears more as a political maneuver than a well-considered policy.

The lack of detailed implementation plans, potential overlap with existing institutions, and the timing of the announcement raised questions about its feasibility and necessity. For the proposal to be credible, it must be supported by a clear strategy, specific objectives, and a commitment to addressing past initiative shortcomings like those seen with MASLOC.

Without these elements, the Women’s Bank risks being perceived as another unfulfilled political promise rather than a genuine effort to empower women economically.

Source: Asaaseradio.com

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More