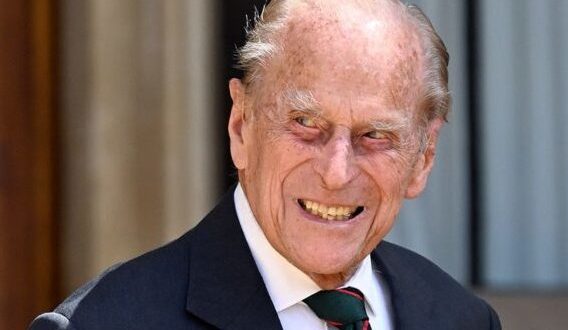

The Duke of Edinburgh, the Queen’s “strength and stay” for 73 years, has died aged 99.

Flags on landmark buildings in Britain were being lowered to half-mast as a period of mourning was announced.

Prince Philip’s health had been slowly deteriorating for some time. He announced he was stepping down from royal engagements in May 2017, joking that he could no longer stand up. He made a final official public appearance later that year during a Royal Marines parade on the forecourt of Buckingham Palace.

Since then, he was rarely seen in public, spending most of his time on the Queen’s Sandringham estate in Norfolk, though moving to be with her at Windsor Castle during the lockdown periods throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and where the couple quietly celebrated their 73rd wedding anniversary in November 2020. He also celebrated his 99th birthday in lockdown at Windsor Castle.

The duke spent four nights at King Edward VII hospital in London before Christmas 2019 for observation and treatment in relation to a “pre-existing condition”.

Despite having hip surgery in April 2018, he attended the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle a month later and was seen sitting beside the Queen at a polo match at Windsor Great Park in June. He and the Queen missed Prince Louis of Cambridge’s christening in July 2018, but he was seen attending Crathie Kirk near Balmoral in August, and driving his Land Rover in the surrounding Scottish countryside in September.

Despite living quietly out of the public eye, he made headlines when involved in a car crash in January 2019. Two women needed hospital treatment after he was apparently dazzled by the low sun as he pulled out of a driveway on the Sandringham estate. A nine-month-old baby boy in the other vehicle was unhurt. The Crown Prosecution Service decided it was not in the public interest to prosecute the duke after he later voluntarily surrendered his driving license.

Born on the island of Corfu, Prince Philip, who once described himself as “a discredited Balkan prince of no particular merit or distinction”, played a key role in the development of the modern monarchy in Britain.

Though never officially given the title of prince consort, he lived a life of relentless royal duty, relinquishing his promising naval career, which some believed could have seen him rise to become First Sea Lord, for a role requiring him to walk several feet behind his wife.

Having made this choice, he immersed himself wholeheartedly in national life, carving out a unique public role. He was the most energetic member of the royal family with, for many decades, the busiest engagements diary.

Even when well-advanced in years, he could be seen on walkabouts hoisting small children over security barriers to enable them to present their posies to his wife.

Often he received little public recognition for his endeavors. In part, this was due to his uncomfortable relationship with the press, whom he labeled “bloody reptiles” and whose coverage often focused on his gaffes. He once told the former Conservative MP and biographer Gyles Brandreth: “I have become a caricature. There we are. I’ve just got to accept it.”

The duke could be blunt and outspoken to the point of offensiveness. He claimed to have coined the word “dontopedalogy”: a talent for putting one’s foot in one’s mouth. Prone to bad-tempered outbursts, he never suffered fools gladly. Equally, he could be charming, engaging, and witty – and displayed such genuine curiosity on his official visits that his hosts were flattered.

While constitutionally excluded from major areas of the Queen’s professional life – he held no constitutional role other than as a privy counselor and saw no state papers – he set about modernizing a monarchy he feared could end up as a museum piece.

It was at his instigation that the practice of presenting debutantes at court was abolished in 1958. He initiated informal palace lunches to which guests from a variety of backgrounds were invited. Garden parties were broadened.

He chaired the Way Ahead Group – composed of leading royal family members and their advisers – to analyze and avert criticism of the institution.

The Queen, who deferred to him in private, would say: “What does Philip think?” on any major matter concerning the royal household. Big decisions, including her, finally agreeing to pay tax on her private income, the abolition of the royal yacht Britannia, and her letter to Charles and Diana suggesting an early divorce were taken after consultation with the duke, according to insiders.

He set out his views on the monarchy on several occasions, recognizing it could not be all things to all people and therefore would always find itself in a position of compromise – or risk being kicked from both sides. But, he argued: “People still respond more easily to symbolism than to reason.” People instinctively understood the idea of a representative rather than a governing leader, and it was important for national identity, he maintained.

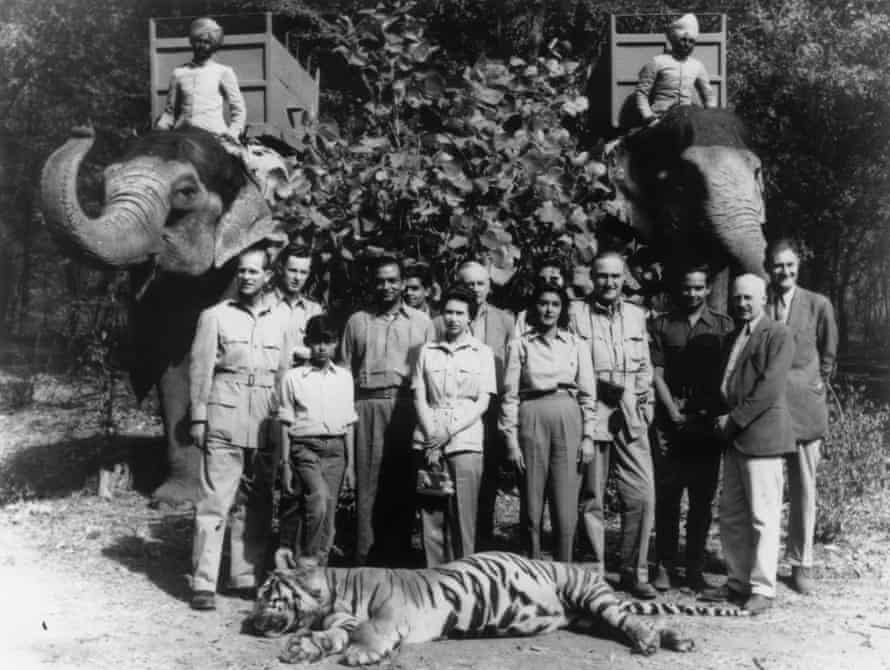

He had a keen interest in religion and conservation, despite dispatching a 2.5-meter (8ft) tiger with a single shot on an official visit to India in 1961, the same year he became president of the World Wildlife Fund UK.

Industry, science, and nature were other passions. One of his most famous speeches was in 1961 when he told leading industrialists: “Gentlemen, I think it is time we pulled our fingers out.” And he loved gadgets.

From the outset he took a keen interest in young people through the Duke of Edinburgh award, which he launched in 1956, inspired by his school days, and organizations such as the National Playing Fields Association and the Outward Bound Trust.

With his youthful good looks and sporting prowess, Philip was a pin-up. He played polo until, in 1971, injury forced him to retire, after which he took up four-in-hand carriage driving – a coach with four horses – which he continued to compete in at international level well into his 80s.

He was a crack shot, a qualified pilot and an accomplished sailor. As the searchlight control officer on the battleship HMS Valiant, he was mentioned in dispatches in 1941 for his role in the Battle of Matapan against the Italian fleet. His wartime service also saw him present at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay in 1945.

His love of the outdoors and physical pursuit was nurtured in childhood at Gordonstoun, the Morayshire school founded by Kurt Hahn, which encouraged self-reliance in pupils. Hahn had a profound influence on the young prince, who rarely saw his parents as a child.

Born at the family home of Mon Repos, apparently on the kitchen table, on Corfu on 10 June 1921, Philip was the youngest child and only son of Prince Andrew of Greece, an officer in the Greek army, and Princess Alice of Battenberg. The family fled when his father was charged with high treason in the aftermath of the heavy defeat of the Greeks by the Turks. They were evacuated in a British warship, with one-year-old Philip being carried in a makeshift cot fashioned from an orange box.

He had an unsettled and peripatetic childhood. His parents separated; his father settling in Monte Carlo where he amassed significant gambling debts, and his mother, who was deaf, going on to found an order of nuns before becoming depressed and being admitted to an asylum. He later said of his family’s break-up: “I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.”

Distantly related to the Queen – they were third cousins – their paths crossed several times before he became a serious suitor in 1946, though she was said to have fallen in love with him when she was 13.

A highly ambitious and complex man, he faced many obstacles in the early days of marriage at the palace. With no money and no title, the establishment thought him a little “below the salt”. George VI was dismayed his daughter wanted to marry the first man she had met and thought her too young. Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother, and never knowingly subtle, mischievously referred to him as “the Hun”, a reference to his mixed Danish, Russian and German heritage. Her brother, David Bowes-Lyon, dismissed him as “a German”.

Courtiers saw him as an outsider – with barely a suit to his name – and a little too Teutonic.

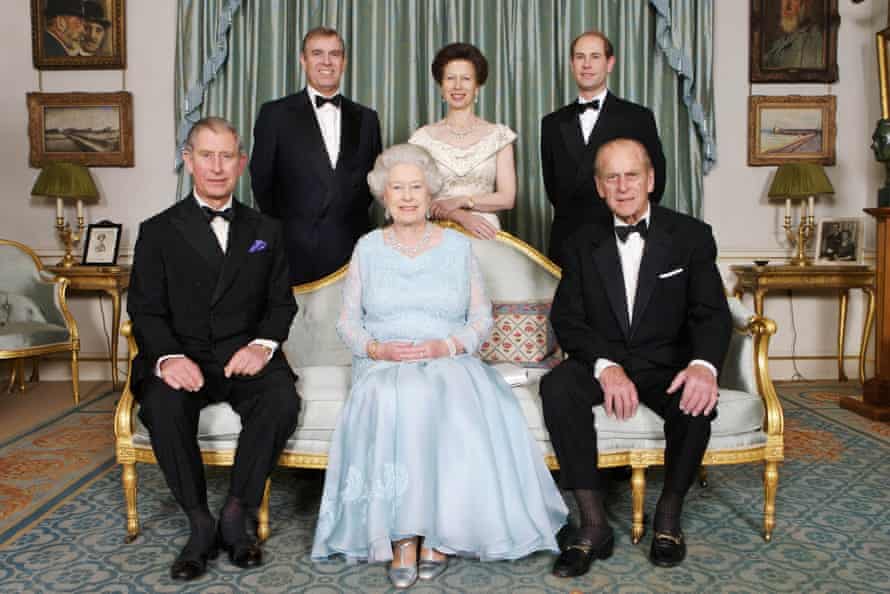

But he succeeded in overcoming prejudice and set about creating a role in which he would become the linchpin of palace life. Describing her reliance on him, the Queen said in a speech to celebrate their golden wedding in 1997: “He is someone who doesn’t take easily to compliments. But he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years, and I, and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know.”

The bishop of London, Richard Chartres, once told the unauthorized biographer Graham Turner: “If one of the standard English aristocrats had married the Queen it would have bored everyone out of their minds.”

The Duke of Edinburgh was many things, but one thing he was not was boring.

Source: The Guardian

The Duke of Edinburgh, the Queen’s “strength and stay” for 73 years, has died aged 99.

Flags on landmark buildings in Britain were being lowered to half-mast as a period of mourning was announced.

Prince Philip’s health had been slowly deteriorating for some time. He announced he was stepping down from royal engagements in May 2017, joking that he could no longer stand up. He made a final official public appearance later that year during a Royal Marines parade on the forecourt of Buckingham Palace.

Since then, he was rarely seen in public, spending most of his time on the Queen’s Sandringham estate in Norfolk, though moving to be with her at Windsor Castle during the lockdown periods throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and where the couple quietly celebrated their 73rd wedding anniversary in November 2020. He also celebrated his 99th birthday in lockdown at Windsor Castle.

The duke spent four nights at King Edward VII hospital in London before Christmas 2019 for observation and treatment in relation to a “pre-existing condition”.

Despite having hip surgery in April 2018, he attended the wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle a month later and was seen sitting beside the Queen at a polo match at Windsor Great Park in June. He and the Queen missed Prince Louis of Cambridge’s christening in July 2018, but he was seen attending Crathie Kirk near Balmoral in August, and driving his Land Rover in the surrounding Scottish countryside in September.

Despite living quietly out of the public eye, he made headlines when involved in a car crash in January 2019. Two women needed hospital treatment after he was apparently dazzled by the low sun as he pulled out of a driveway on the Sandringham estate. A nine-month-old baby boy in the other vehicle was unhurt. The Crown Prosecution Service decided it was not in the public interest to prosecute the duke after he later voluntarily surrendered his driving license.

Born on the island of Corfu, Prince Philip, who once described himself as “a discredited Balkan prince of no particular merit or distinction”, played a key role in the development of the modern monarchy in Britain.

Though never officially given the title of prince consort, he lived a life of relentless royal duty, relinquishing his promising naval career, which some believed could have seen him rise to become First Sea Lord, for a role requiring him to walk several feet behind his wife.

Having made this choice, he immersed himself wholeheartedly in national life, carving out a unique public role. He was the most energetic member of the royal family with, for many decades, the busiest engagements diary.

Even when well-advanced in years, he could be seen on walkabouts hoisting small children over security barriers to enable them to present their posies to his wife.

Often he received little public recognition for his endeavors. In part, this was due to his uncomfortable relationship with the press, whom he labeled “bloody reptiles” and whose coverage often focused on his gaffes. He once told the former Conservative MP and biographer Gyles Brandreth: “I have become a caricature. There we are. I’ve just got to accept it.”

The duke could be blunt and outspoken to the point of offensiveness. He claimed to have coined the word “dontopedalogy”: a talent for putting one’s foot in one’s mouth. Prone to bad-tempered outbursts, he never suffered fools gladly. Equally, he could be charming, engaging, and witty – and displayed such genuine curiosity on his official visits that his hosts were flattered.

While constitutionally excluded from major areas of the Queen’s professional life – he held no constitutional role other than as a privy counselor and saw no state papers – he set about modernizing a monarchy he feared could end up as a museum piece.

It was at his instigation that the practice of presenting debutantes at court was abolished in 1958. He initiated informal palace lunches to which guests from a variety of backgrounds were invited. Garden parties were broadened.

He chaired the Way Ahead Group – composed of leading royal family members and their advisers – to analyze and avert criticism of the institution.

The Queen, who deferred to him in private, would say: “What does Philip think?” on any major matter concerning the royal household. Big decisions, including her, finally agreeing to pay tax on her private income, the abolition of the royal yacht Britannia, and her letter to Charles and Diana suggesting an early divorce were taken after consultation with the duke, according to insiders.

He set out his views on the monarchy on several occasions, recognizing it could not be all things to all people and therefore would always find itself in a position of compromise – or risk being kicked from both sides. But, he argued: “People still respond more easily to symbolism than to reason.” People instinctively understood the idea of a representative rather than a governing leader, and it was important for national identity, he maintained.

He had a keen interest in religion and conservation, despite dispatching a 2.5-meter (8ft) tiger with a single shot on an official visit to India in 1961, the same year he became president of the World Wildlife Fund UK.

Industry, science, and nature were other passions. One of his most famous speeches was in 1961 when he told leading industrialists: “Gentlemen, I think it is time we pulled our fingers out.” And he loved gadgets.

From the outset he took a keen interest in young people through the Duke of Edinburgh award, which he launched in 1956, inspired by his school days, and organizations such as the National Playing Fields Association and the Outward Bound Trust.

With his youthful good looks and sporting prowess, Philip was a pin-up. He played polo until, in 1971, injury forced him to retire, after which he took up four-in-hand carriage driving – a coach with four horses – which he continued to compete in at international level well into his 80s.

He was a crack shot, a qualified pilot and an accomplished sailor. As the searchlight control officer on the battleship HMS Valiant, he was mentioned in dispatches in 1941 for his role in the Battle of Matapan against the Italian fleet. His wartime service also saw him present at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay in 1945.

His love of the outdoors and physical pursuit was nurtured in childhood at Gordonstoun, the Morayshire school founded by Kurt Hahn, which encouraged self-reliance in pupils. Hahn had a profound influence on the young prince, who rarely saw his parents as a child.

Born at the family home of Mon Repos, apparently on the kitchen table, on Corfu on 10 June 1921, Philip was the youngest child and only son of Prince Andrew of Greece, an officer in the Greek army, and Princess Alice of Battenberg. The family fled when his father was charged with high treason in the aftermath of the heavy defeat of the Greeks by the Turks. They were evacuated in a British warship, with one-year-old Philip being carried in a makeshift cot fashioned from an orange box.

He had an unsettled and peripatetic childhood. His parents separated; his father settling in Monte Carlo where he amassed significant gambling debts, and his mother, who was deaf, going on to found an order of nuns before becoming depressed and being admitted to an asylum. He later said of his family’s break-up: “I just had to get on with it. You do. One does.”

Distantly related to the Queen – they were third cousins – their paths crossed several times before he became a serious suitor in 1946, though she was said to have fallen in love with him when she was 13.

A highly ambitious and complex man, he faced many obstacles in the early days of marriage at the palace. With no money and no title, the establishment thought him a little “below the salt”. George VI was dismayed his daughter wanted to marry the first man she had met and thought her too young. Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother, and never knowingly subtle, mischievously referred to him as “the Hun”, a reference to his mixed Danish, Russian and German heritage. Her brother, David Bowes-Lyon, dismissed him as “a German”.

Courtiers saw him as an outsider – with barely a suit to his name – and a little too Teutonic.

But he succeeded in overcoming prejudice and set about creating a role in which he would become the linchpin of palace life. Describing her reliance on him, the Queen said in a speech to celebrate their golden wedding in 1997: “He is someone who doesn’t take easily to compliments. But he has, quite simply, been my strength and stay all these years, and I, and his whole family, and this and many other countries, owe him a debt greater than he would ever claim, or we shall ever know.”

The bishop of London, Richard Chartres, once told the unauthorized biographer Graham Turner: “If one of the standard English aristocrats had married the Queen it would have bored everyone out of their minds.”

The Duke of Edinburgh was many things, but one thing he was not was boring.

Source: The Guardian

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More

Home Of Ghana News Ghana News, Entertainment And More